September 1457: Battle of Albulena; Teutonic Order Recaptures Malbork Town

Sultan Mehmed II had not abandoned his efforts to subjugate Albania. After the partial success of 1455 when his forces helped capture Berat fortress, and the devastating loss at Oranik in 1456, the Sultan decided to launch a much larger campaign in 1457. By the end of May, a huge Ottoman army with force estimates between 50,000 and 80,000 men began its march toward Albania.

The Sultan appointed two commanders for this invasion, both chosen for their intimate knowledge of Albanian terrain and tactics. Ishak Bey Evrenoz was an experienced general who had crushed Gjon Kastrioti's rebellion in 1430 and led the successful counterattack at Berat two years earlier. As his second commander, for the second year in a row, the Sultan chose a traitor from Skanderbeg's own ranks — this time Hamza Kastrioti, Skanderbeg's own nephew.

Hamza's betrayal stung particularly deep. He had fought alongside Skanderbeg since 1443, when both men abandoned Ottoman service to join the Albanian resistance. For over a decade, Hamza had been one of Skanderbeg's most trusted officers. His defection may have been prompted by personal ambition — in 1456, Skanderbeg had fathered a son who would displace Hamza as heir. Whatever his motivations, Hamza now brought to the Ottoman side invaluable knowledge of his uncle's tactics and the loyalty of several other disaffected Albanian nobles. The Sultan promised him control over much of Albania once conquered.

The Ottoman army entered Albania in May. Skanderbeg initially harassed the advance forces, but when the main army arrived, he recognized the impossibility of direct confrontation. With only 8,000 to 10,000 men at his disposal, he faced an enemy that greatly outnumbered him. More troubling still, both Ottoman commanders knew his usual tactics intimately — the feigned retreats, the mountain ambushes, the sudden strikes from unexpected directions.

Skanderbeg adapted with a radical new strategy. Rather than keeping his forces together as a unified army, he split them into multiple independent groups. Each unit received orders to march through different mountain paths and forests, supplied by local villagers and hidden supply depots. They were forbidden to assemble or attack unless Skanderbeg gave the signal. For the three summer months these scattered bands shadowed the Ottoman army while remaining invisible in the Albanian highlands.

The Ottomans marched through the Mat valley, pillaging as they went, increasingly frustrated by Skanderbeg's apparent disappearance. Ishak Bey hesitated to besiege Krujë, Albania's main fortress, without first determining Skanderbeg's fate. Instead, the Ottoman army made camp at Albulena, north of Mount Tumenishta. They fortified their position, especially on the northern approaches, while leaving the eastern side that faced the dense forests less defended.

As weeks passed with no sign of Albanian forces, rumors spread that Skanderbeg had fled, unable to face such overwhelming numbers. The Venetians in Durrës eagerly promoted these stories. Some claimed his own men had betrayed him. The Ottoman commanders began to believe they had won without fighting a major battle. By late August, confident in their victory, they prepared to withdraw.

This was exactly what Skanderbeg had been waiting for. On September 2, judging the moment right, he gave the signal for his scattered forces to converge on Tumenishta — the mountain overlooking the Ottoman camp's weakest point. The Albanian troops assembled in darkness, then split into three assault groups. Skanderbeg himself led a band of trusted men to eliminate the Ottoman sentries, but one guard spotted them and fled toward the camp shouting warnings.

With surprise partially lost, Skanderbeg ordered an immediate attack. The Albanians charged down the mountainside, creating tremendous noise by clashing their weapons and tools together, making their numbers seem far greater than they were. The Ottoman camp erupted in chaos. Soldiers, roused from sleep and convinced they faced a massive assault, panicked despite their numerical superiority.

Hamza tried desperately to rally his men, assuring them the Albanians were few, while Ishak Bey attempted to send reinforcements. But the arrival of the other Albanian contingents from multiple directions convinced the Ottomans they were surrounded. The organized Ottoman force dissolved into a fleeing mob. In the slaughter that followed, the Albanians killed as many as 15,000 Ottoman soldiers and captured another 15,000, along with twenty-four standards and all the wealth in the camp. Among the prisoners was Hamza Kastrioti himself, while Ishak Bey managed to escape.

The Battle of Albulena would be remembered as Skanderbeg's most brilliant victory. After more than a decade of continuous warfare, it reinvigorated Albanian resistance.

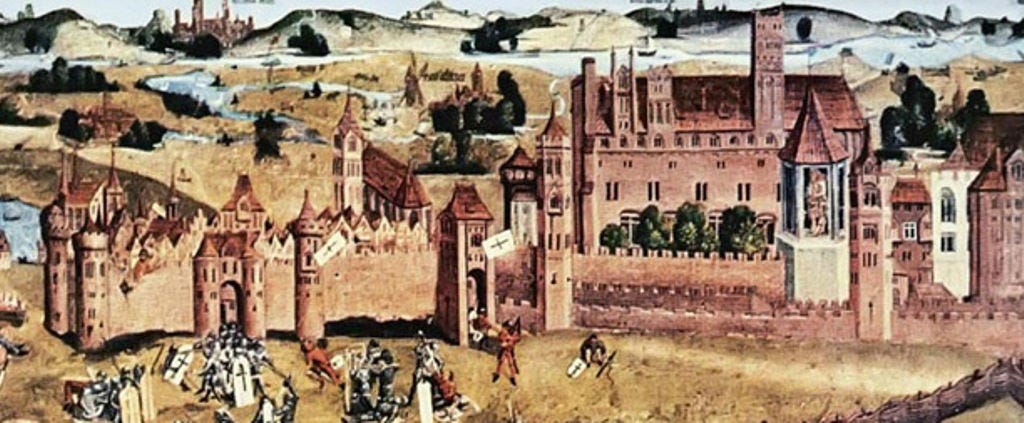

When King Casimir IV rode triumphantly through Malbork's gates in June 1457, many believed the Thirteen Years' War was nearing its end. The Teutonic Order had lost its capital, its Grand Master had fled, and Polish banners now flew over the mightiest fortress in Prussia. Yet this apparent victory would prove premature.

From his new seat in Königsberg, Grand Master Ludwig von Erlichshausen immediately began planning a counter-offensive. The Order may have lost Malbork, but it retained considerable military resources and — crucially — the loyalty of several experienced mercenary commanders. Chief among these was Bernard Szumborski, a Moravian captain who, unlike his Bohemian compatriot Ulrich Czerwonka, had remained faithful to his Teutonic employers despite their chronic payment problems.

By August 1457, Szumborski's professional army was on the march toward Malbork. Near Sępopole, they encountered a hastily assembled pospolite ruszenie — a general call to arms that summoned Polish landowners to fulfill their military obligations. The result was predictable: Szumborski's disciplined mercenaries, scattered the poorly organized Polish forces with ease. Once again, as at Chojnice three years earlier, professional soldiers had demonstrated their crushing superiority over the old mobilization system.

In late September, Szumborski's army reached Malbork. What followed wasn't a conventional siege. The citizens of Malbork town, led by their mayor Bartholomäus Blume, opened their gates to the Teutonic forces without resistance. This act of betrayal — or loyalty, depending on one's perspective — revealed the fundamental weakness in Poland's position in Malbork. The townspeople were overwhelmingly German in language and culture, bound to the Teutonic Order by centuries of shared history. Their submission to Casimir just three months earlier had been a pragmatic bow to superior force, not a change of heart.

A strategically bizarre situation arose. The town of Malbork was now in Teutonic hands, but the great castle remained under Polish control, garrisoned by Czerwonka's mercenaries and Polish troops. Szumborski lacked the heavy artillery and numbers needed to storm the fortress, so he settled in for a siege, using the town's resources to sustain his blockade.

Polish reinforcements soon arrived to counter-blockade the Teutonic-held town, but they too lacked the strength for a direct assault. The result was a peculiar double siege: Polish forces surrounding a Teutonic-occupied town that was itself besieging a Polish-held castle.

As this stalemate promised to drag on indefinitely, King Casimir made a significant decision. Recognizing that the defense of Malbork required not just military skill but political reliability, he relieved Czerwonka of his command and appointed Ścibor Chełmski in his place. Chełmski was a prominent Polish nobleman who had served as podkomorzy (chamberlain) of Poznań and had played a crucial role in securing the loans from Gdańsk that had made the purchase of Malbork possible — a man whose loyalty to the Crown was beyond question.