August 1457: French Raid on Sandwich; Gdańsk vs Denmark; Mainz Psalter

On August 28, a French force of several thousand men under Pierre de Brézé, Grand Seneschal of Normandy, descended upon Sandwich on the Kent coast. The raiders swept through the prosperous port town, looting and burning as they went. Much of Sandwich was reduced to smoking ruins, its warehouses emptied and its buildings torched. In a display of contempt that would long rankle in English memory, the French were seen playing tennis in the charred remains of the town before Sir Thomas Kyriell finally drove them back to their ships. Many of the raiders would not make it home — rough seas in the Channel claimed numerous French lives during the return voyage.

The raid was ostensibly retaliation for English activities in the Channel, particularly those of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. As Captain of Calais since 1456, Warwick commanded about ten ships that engaged French and Burgundian pirates threatening English commerce. Yet the line between fighting piracy and engaging in it was decidedly blurry in these waters, and Warwick's targets included legitimate merchant vessels alongside genuine pirates. Warwick had even seized three Italian ships at Tilbury that carried royal licenses to export English wool, an action that delighted London merchants who resented foreign competition.

Yet Warwick, despite his naval forces and his position at Calais, had made no attempt to intercept Brézé's fleet. His inaction would prove politically astute. The successful French raid, rather than damaging his reputation, only enhanced his standing. He had already won popularity among English merchants for his aggressive stance against foreign shipping. Now the government's failure to protect Sandwich made the Yorkist earl appear even more necessary for England's defense.

For Queen Margaret, the raid was a diplomatic disaster. Brézé was no random French commander but a key figure in her attempts to secure support from Charles VII of France. Originally from Anjou, her father's duchy, Brézé had served as her intermediary in sensitive negotiations with the French court. Margaret had hoped to arrange a new peace treaty that might eventually provide her with French military support against her domestic enemies. Instead, Brézé's attack on Sandwich turned her French connection into a liability. Yorkist propagandists quickly spread rumors that the queen had actually invited the raid to discredit Warwick — a charge that, however baseless, found ready believers among those already suspicious of the French-born queen.

By August 1457, the Thirteen Years' War on land had slowed down. Since the loss of Königsberg two years prior in 1455, Prussia hadn't seen significant military action. The only major city changing hands had been Malbork, and it was sold rather than conquered. Neither side could muster decisive military action that would end the war.

While the fighting had all but stopped on land, the shipping lanes on the Baltic Sea saw more action. Since March 1456, Gdańsk had been issuing privateering licenses to its merchants and sailors, transforming commercial vessels into sanctioned raiders. These privateers, operating under letters of marque from King Casimir IV, targeted Teutonic supply lines and trade routes across the region. The naval engagement off the shores of the island of Bornholm was one of the most dramatic events in this campaign.

On the night of August 14-15, 1457, three Gdańsk privateer ships under captains Jakub Heine, Jocki Lenyn, and Bartz Lenyn encountered a formidable Danish-Livonian convoy of sixteen vessels. Both fleets were returning from Tallinn (Reval) with the Danish convoy carrying vital supplies and reinforcements destined for the beleaguered Teutonic Knights in Prussia.

Denmark's involvement in the conflict stemmed from complex Baltic politics. As the dominant power in the Kalmar Union, Denmark found itself in natural competition with the Hanseatic League, of which Gdańsk was a prominent member. The rivalry had intensified just two months earlier when Christian I was crowned King of Sweden in June 1457, after deposing the previous anti-Kalmar Swedish king Karl Knutsson. Knutsson fled and was given refuge in Gdańsk, giving Christian I yet another reason to oppose the Prussian and Polish cause.

Despite being outnumbered more than five to one, the Gdańsk captains made the audacious decision to attack. Using the cover of darkness to maximum advantage, they struck with the speed and ferocity that would become the hallmark of privateer warfare. The night battle was chaotic and brutal. The smaller, more maneuverable Gdańsk ships darted in and out of the convoy formation, likely engaging individual Danish vessels separately before the larger fleet could coordinate a response.

When dawn broke on August 15, the battle's outcome was clear: a stunning victory for Gdańsk. The privateers had suffered only twelve dead against their enemies' catastrophic losses of around 300 men killed and more than 40 captured, including five Livonian Knights. Sources differ on the number of Danish ships destroyed — some claim one vessel sunk, while Polish accounts boast of six ships sunk and six more captured. Regardless of the exact tally, the convoy was utterly dispersed, its mission a complete failure.

This "greatest sea battle of the war," as Polish historians would later call it, proved that Gdańsk's privateer strategy could deliver strategic results far beyond mere commerce raiding. The victory tightened the naval blockade around the Teutonic state and demonstrated that the Baltic was no longer safe for the Order's allies.

Soon after Europe's first printed book appeared, the partnership that created it had dissolved. In 1455, just as Johannes Gutenberg and his investor Johann Fust completed their monumental 42-line Bible, their collaboration ended in a lawsuit. The court ruled in favor of Fust, who gained control of the printing workshop and equipment, effectively ending the first great printing partnership in Europe.

The technology and equipment that changed hands were immediately put to use. Johann Fust, the victorious businessman, joined forces with Peter Schöffer, a former manuscript scribe who had been Gutenberg's principal workman. Schöffer had testified on Fust's behalf during the lawsuit, and their partnership would soon be cemented further when Schöffer married Fust's daughter. Together, they established Fust & Schöffer, determined to prove they could surpass their former partner's achievements.

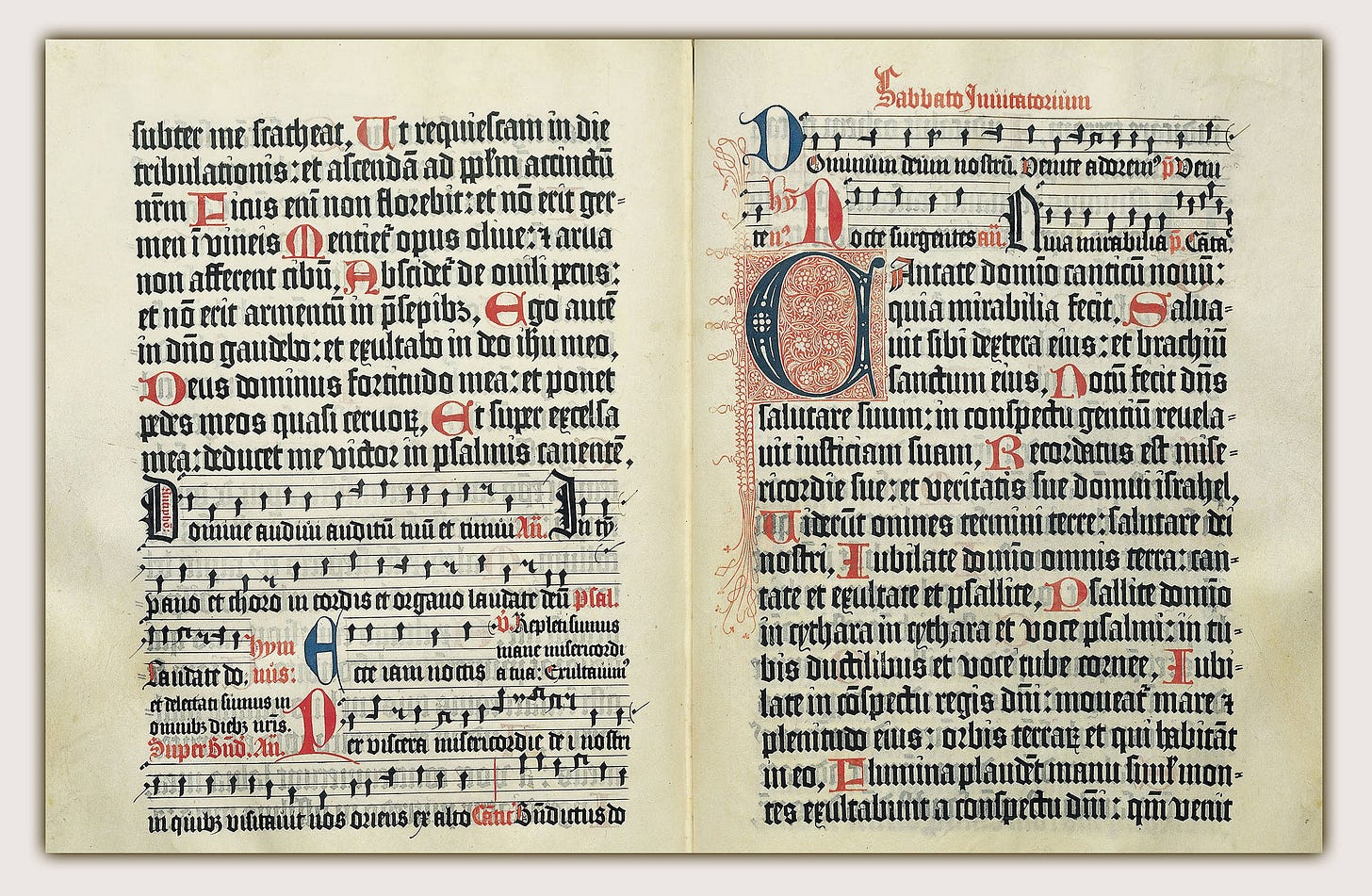

Their first major undertaking was ambitious: a psalter commissioned by the Archbishop of Mainz himself. On August 14, 1457, the Mainz Psalter emerged from their workshop, marking several revolutionary firsts in the history of printing.

Rather than simply using the technology that they acquired, the partners made significant innovations. While Gutenberg's Bible had left spaces for decorative initials to be added by hand, Fust and Schöffer developed an intricate system to print in three colors — black, red, and blue — in a single impression. They created composite, separable printing blocks where letterforms and decorative elements could be inked individually and reassembled like a puzzle before printing. Though this process produced stunning results, it proved too complex and time-consuming for practical use, and even Fust and Schöffer abandoned it in their later works.

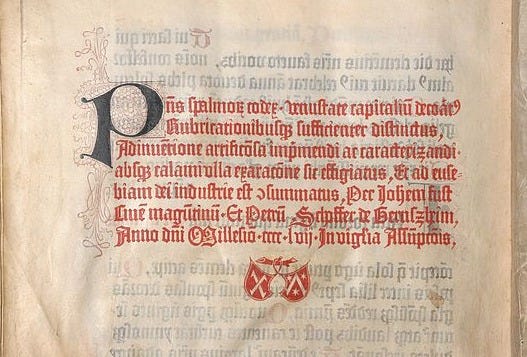

Most significantly, the Psalter contained the first printed colophon in history. Printed at the end of the book in the red ink, it states:

The present codex of the psalms, adorned with the beauty of its capital letters, and sufficiently distinguished by its rubrications, fashioned by a masterful invention of printing and lettering without any ploughing of a pen, and diligently completed for the worship of God, by Johann Fust, citizen of Mainz, and Peter Schoeffer of Gernsheim, in the year of the Lord 1457, on the Vigil of the Assumption.

Interestingly, this first colophon contained a typographical error already in the second word of the text: "spalmorum" instead of "psalmorum" (“of the psalms”).

The Psalter was clearly positioned as a luxury item. All surviving copies were printed on fine vellum rather than paper, suggesting a price comparable to high-quality manuscripts. Though we don't know the exact cost, the use of such expensive materials and the complex printing process indicates this was a book for cathedrals and princes, not ordinary readers. The printing process hasn’t yet driven down the prices of books.