January 1457: Poland Buys More Land; Henry Tudor Is Born; First Witch Trial in Netherlands

King Casimir IV Jagiellon was on a buying spree. Shortly after securing three Prussian castles from the mercenaries fighting for the Teutonic Order, he made another land purchase — though this deal had been years in the making and had nothing to do with the Thirteen Years' War raging in the north.

The Duchy of Oświęcim had been separate from Poland since around 1315, when it split off from the Duchy of Cieszyn. In 1327, its rulers became vassals of Bohemia, placing this historically Polish territory under foreign control. By the mid-15th century, the duchy had become a constant problem on Poland's southern border.

The crisis centered on Duke Jan IV, who had ruled since 1434. He inherited a realm already deep in debt, but proved completely unable to manage his finances. Rather than finding legitimate solutions, Jan IV turned to outright robbery, joining bandit groups that terrorized the borderlands and attacked merchants traveling to Kraków. His crimes posed a serious threat to Polish trade and regional peace.

Casimir IV's response was methodical. In 1453, Polish forces occupied Oświęcim, demonstrating that the duke's misrule would no longer be tolerated. The following year, recognizing where true power lay, the gentry and burghers of the duchy swore oaths of loyalty to the Polish king, effectively abandoning their nominal lord. These acts established Polish dominance in all but name.

The formal transfer came in January 1457, when Duke Jan IV finally agreed to sell his ancestral lands. The price was substantial — 50,000 grzywna in silver, roughly equivalent to £30,000-40,000 in contemporary English currency. For this sum, Casimir acquired the duchy's two towns (Oświęcim and Kęty), two castles, and 45 villages. The purchase not only removed a troublesome neighbor but also began to reverse the long process by which Silesian territories had slipped away from Poland.

When Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, died at Carmarthen Castle in November 1456, his brother Jasper immediately took responsibility for Richmond's thirteen-year-old widow. Margaret Beaufort was six months pregnant at the time, and Jasper offered her the safety of Pembroke Castle, where she could await the birth of her child under his protection.

On 28 January 1457, Margaret gave birth to a son at Pembroke Castle. The birth was difficult — Margaret was of "very small stature," and according to her later funeral sermon, "it seemed a miracle that of so little a personage anyone should have been born at all." The ordeal left her unable to bear more children. The baby was sickly, surviving his early years only through Margaret's devoted care.

According to Welsh tradition, Jasper wanted the boy christened Owen after his grandfather, Owen Tudor. But Margaret insisted that her son be named Henry in honour of the king. As his father's posthumous child, the infant was styled Earl of Richmond from birth.

At the time, no one imagined that this obscure scion of the royal house, born to a child-widow in a Welsh castle, would amount to anything remarkable. The Beauforts' claim to the throne was tenuous at best, deriving from John of Gaunt's legitimized bastards. Yet this sickly infant would one day become Henry VII, founder of the mighty Tudor dynasty.

In 1457, the northern city of Groningen witnessed the first recorded witch trial in what would become the Netherlands. Twenty women and one man were condemned and executed for witchcraft. While the specific records and names of the victims have been lost, the trial likely followed the patterns that were beginning to emerge across 15th-century Europe.

We often think of witch hunts as belonging to the Middle Ages, but the Groningen trial actually stood at the threshold of the Early Modern period, when the great European witch craze was just beginning to take shape. Before the 15th century, there was no systematic practice of hunting and prosecuting witches. The Catholic Church had long maintained, through documents like the Canon Episcopi (around 900 AD), that belief in witchcraft was largely a pagan superstition — a delusion to be corrected through teaching, not execution.

The 14th century France saw isolated witch trials, but organized persecution began in Valais, an alpine valley east of Lake Geneva, now part of Switzerland. Between 1428 and 1459, this region witnessed the first mass witch trials in European history, establishing a deadly template that would spread across the continent. On 7 August 1428, authorities in Leuk issued a formal proclamation outlining procedures for witch trials. According to this document, "public talk or slander of three or four neighbours" sufficed for arrest and imprisonment. With testimony from five neighbors, torture could be applied to extract confessions. Most crucially, anyone named by at least three tortured "witches" could themselves be arrested and tortured, creating a vicious cycle of accusations. Unlike later witch hunts, it was estimated that two-thirds of those accused in Valais were male and one-third female.

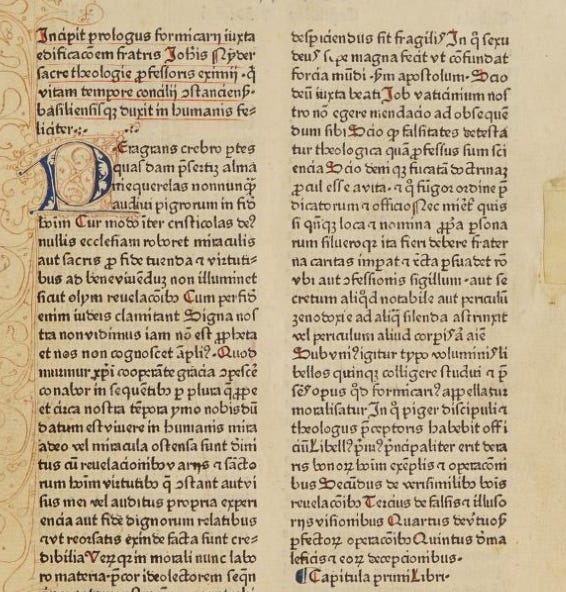

The intellectual framework for this new persecution was taking shape alongside these early trials. Between 1436 and 1438, the Dominican theologian Johannes Nider completed his Formicarius. Written as a dialogue between a theologian and a skeptical student, Nider's work was based on testimony he gathered from secular and clerical authorities, including accounts from Peter of Bern who had conducted witch trials in the Simme Valley, north of Valais in Switzerland. Significantly, Nider was one of the first to transform the idea of sorcery from learned male magic to something practiced by uneducated, common women — a shift he justified by pointing to what he considered women's inferior physical, mental, and moral capacity. While Nider remained skeptical about claims that witches could fly by night, his work established the theological justification for viewing witchcraft as a diabolical heresy demanding the harshest punishment.

By 1457, this lethal combination of legal precedent and theological theory had spread from the Alpine valleys into the northern Swiss cantons and the German lands. Groningen's trial demonstrates how quickly these ideas traveled along the trade routes of the Hanseatic League, transforming local witch trials into a pan-European persecution.