January 1455: Romanus Pontifex; Winter Campaign in Poland; Kyōtoku Incident

January 1455 was an eventful month. So eventful in fact, that this post will probably turn out to be the longest one in the blog so far. In large part this is due to the events in Japan, which require a relatively long explanation just to set the stage.

But let's start with the European continent which also saw a few important developments.

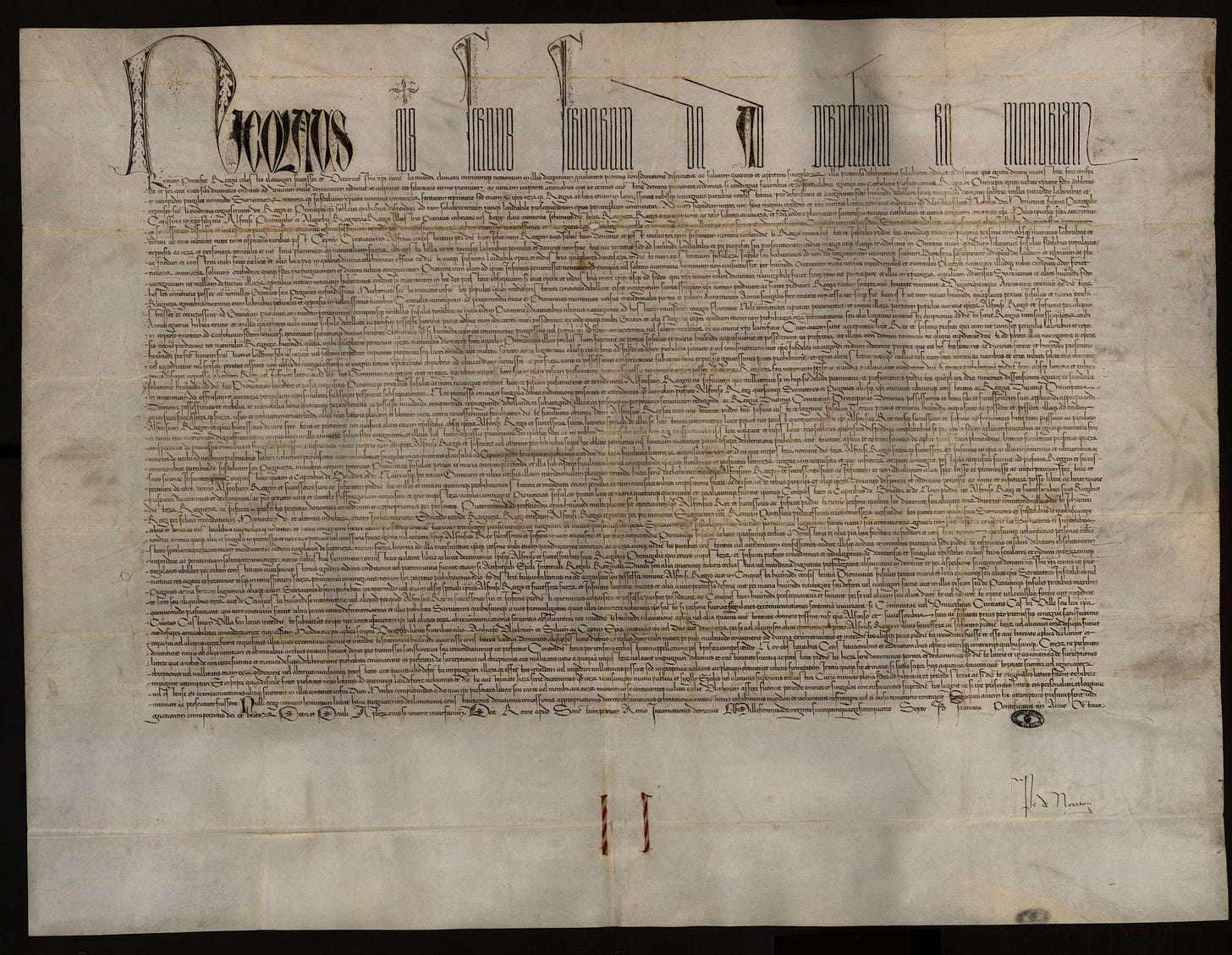

On January 8, Pope Nicholas V issued one of the most consequential documents of the age of exploration. The papal bull, Romanus Pontifex, set the legal and ethical guidelines for Europe's expansion into Africa and other regions.

For over four decades, Prince Henry the Navigator had sponsored Portuguese expeditions along Africa's western coast. Starting from their capture of the North African city of Ceuta in 1415, Portuguese explorers had been systematically advancing further and further along the African coast. By the 1450s, Portuguese caravels had pushed south of Cape Bojador and were regularly trading with West African communities, bringing back gold, ivory, and increasingly, slaves.

Portugal's neighbor, the Kingdom of Castile, with its own Atlantic ambitions, was challenging Portuguese claims to various African territories and trade routes. This led to several incidents between the two fleets.

Pope Nicholas V's decision to favor Portugal reflected both politics and piety. King Afonso V portrayed their expansion as part of the broader Christian struggle against Islamic powers. The bull explicitly praised Portuguese victories against "the Muslims of North Africa" and positioned further exploration as a continuation of the crusading tradition.

The terms of Romanus Pontifex were sweeping in their scope and implications. The bull granted Portugal the exclusive right to "invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever" in the regions they discovered. More ominously, it authorized the Portuguese "to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods."

Importantly, the bull required that Portuguese expansion include a missionary component. Colonial authorities were commanded not only to build "churches, monasteries, and holy places" but also to work actively for the conversion of local populations. This religious mandate provided a moral justification for the otherwise largely commercial enterprise.

For Pope Nicholas V, Romanus Pontifex served multiple purposes in his broader struggle against Ottoman expansion. By encouraging Portuguese exploration and conquest, he hoped to find new routes to Asian Christian communities and potential allies against Islamic powers. The bull specifically mentioned the goal of reaching "the Indians who are said to worship the name of Christ"—likely a reference to the legendary Prester John, believed to rule a Christian kingdom somewhere in Africa or Asia.

The document would have consequences far beyond its immediate purpose. Romanus Pontifex, along with earlier bulls like Dum Diversas (1452), provided legal and religious justification for centuries of European conquests and slave trade. At the time of its issuance, however, such practices were viewed differently. Slavery existed throughout the world as an accepted institution, and the papal authorization was seen justified by its higher purpose.

On the other end of Europe, King Casimir IV of Poland, had spent the autumn months rebuilding his military capabilities. After issuing the Nieszawa Statutes designed to appease the gentry (szlachta), the king had assembled a formidable force of nearly 30,000 conscripts, augmented by approximately 3,000 experienced Czech mercenaries.

Despite the onset of winter, Casimir made the bold decision to launch an immediate offensive against the Teutonic stronghold of Łasin (Lessen). The strategic logic was sound: the town controlled crucial routes into the contested Pomeranian territories, and its capture could potentially unlock access to other Teutonic positions in the region.

Heavy autumn rains slowed the army's advance to a crawling 4-5 kilometers per day, while the onset of freezing temperatures created acute shortages of firewood, food, and forage for the thousands of horses. And when the army arrived at its destination, it found itself unable to take it. Casimir's army, which struggled with sieges throughout 1454, was fundamentally unsuited for siege warfare against well-fortified positions. The force lacked adequate artillery—the heavy cannons that were becoming essential for reducing 15th-century fortifications. Without these tools, the Polish siege devolved into an ineffective blockade.

On January 9, 1455, Polish forces attempted a direct assault on Łasin's walls. The attack ended in complete failure. Recognizing the deteriorating situation, King Casimir turned to diplomacy. On the same day, a Teutonic delegation arrived at the Polish camp near the village of Szczepanki to begin peace negotiations.

The negotiations revealed the profound gulf separating the two sides. The Order presented uncompromising demands: the complete withdrawal of all Polish forces from Prussia and the dissolution of the Prussian Confederation which they considered illegal. The Order refused to consider even a temporary truce, likely sensing that the Polish army's desperate situation could be exploited for maximum advantage.

Polish and Prussian representatives rejected these demands outright. The talks collapsed by January 10, achieving nothing. The fundamental incompatibility of the core demands—the Order seeking a complete reversal of the events of 1454, while Poland and the Prussian Confederation remained committed to Prussian incorporation into the Polish kingdom—made compromise impossible.

With diplomacy exhausted and his army's position increasingly untenable, King Casimir ordered a withdrawal from Łasin around January 20. The main body of the pospolite ruszenie retreated through Toruń, while the king left Polish mercenary garrisons in various strategic castles to maintain some presence in the contested territories.

Far from the winter battlefields of Central Europe, January 1455 witnessed the violent culmination of a very different power struggle in the eastern provinces of Japan. The Kyōtoku Incident, which began with a revenge-driven assassination, was rapidly escalating into a conflict that would reshape the political landscape of the Kantō region for decades to come.

To understand the crisis, it's essential to grasp the complex governmental structure of 15th-century Japan. The country was nominally ruled by shoguns from the Ashikaga clan, based in the capital city of Kyoto. However, the eastern territories—including the region around modern-day Tokyo and everything northeast—comprised a semi-autonomous administrative unit called the Kamakura-fu, governed from the ancient city of Kamakura (in the south of the modern-day Greater Tokyo metropolitan area).

This eastern territory was administered by an official called the Kantō Kubō, a position held by a separate branch of the Ashikaga clan that was often at odds with the main shogunal line in Kyoto. Alongside the Kubō served another official, the Kantō Kanrei, traditionally a member of the powerful Uesugi clan who functioned as a deputy but maintained closer ties to the Kyoto government. This arrangement created an inherent tension: the Kubō represented regional autonomy, while the Kanrei served as Kyoto's watchdog.

The seeds of the current crisis lay in events from two decades earlier. In the 1430s, the previous Kantō Kubō, Ashikaga Mochiuji, had openly rebelled against the shogun in Kyoto. The conflict ended with Mochiuji's defeat and forced seppuku in 1439, largely through the actions of then Kantō Kanrei, who supported Kyoto against his nominal superior.

The current players in this deadly game were the sons of those earlier protagonists. Ashikaga Shigeuji, the present Kantō Kubō, was Mochiuji's surviving son, carrying a burning desire for vengeance against the Uesugi clan. His target was Uesugi Noritada, the young Kantō Kanrei whose father had played a crucial role in the previous Kubō's downfall.

On the night of December 27, 1454 (January 15, 1455 according to the Gregorian calendar), Shigeuji sprang his trap. He summoned Uesugi Noritada to his mansion in Kamakura under some urgent pretext. Once inside, the twenty-two-year-old Kanrei was ambushed and murdered by Shigeuji's retainers. Simultaneously, other forces loyal to the Kubō attacked the Kanrei's official residence, killing several key Uesugi officials and retainers.

The assassination was not merely a personal revenge killing but a calculated act designed to shatter Uesugi power and signal a complete break with Kyoto's oversight. The reaction was swift and devastating. The surviving Uesugi leaders, rallying around Noritada's younger brother who was appointed as the new Kanrei, mobilized their forces and allies across multiple provinces. The Kyoto government branded Shigeuji a rebel and ordered military action against him.

Rather than wait for this coalition to assemble against him, Shigeuji seized the initiative. On January 5, he marched his army out of Kamakura, aiming to strike preemptively at Uesugi strongholds in neighboring provinces. The gamble initially appeared to pay off spectacularly.

When Uesugi forces attempted to retake the undefended Kamakura on January 6, they were intercepted and defeated by Shigeuji's rearguard at Shimokawara. More significantly, when the main Uesugi army—reportedly numbering around 2,000 cavalry—confronted Shigeuji's smaller force of approximately 500 cavalry at Bubaigawara on January 21-22, the Kubō achieved a crushing victory despite being outnumbered.

Yet these tactical victories could not overcome strategic realities. While Shigeuji was winning battles in the field, the shogunate forces captured and devastated Kamakura itself. The ancient city, which had served as the seat of eastern power for over a century, was put to the torch.

Faced with the loss of his traditional capital and the mobilization of overwhelming forces against him, Shigeuji was compelled to abandon central Kantō entirely. By the end of January 1455, he had retreated northward to the town of Koga in the North of Kanto region, where he enjoyed stronger support from allied clans like the loyal Yūki family.

From this new base, Shigeuji would continue his defiant struggle as the "Koga Kubō," establishing a rival center of authority that challenged both the Uesugi clan and the Kyoto government. His survival and the establishment of this alternative power structure ensured that the Kantō region would remain divided and conflict-ridden for decades to come.